(This post takes 12 minutes and 1 second to read)

A former colleague, a professor who spent years teaching writing, emailed me a complaint: "Why do you think you're so much better at teaching writing than everybody else?"

Ouch.

This email made me realize that the often-exasperated tone I use when writing about the relative failures of college-writing pedagogy (and writing instruction) to prepare students to write well when they go to work may give the impression that I think I'm a better writing teacher, that I think I know more about teaching writing, that I depreciate what other writing teachers are teaching.

But that's not at all how I feel or how I think about other writing teachers or my own finite set of writing teaching abilities.

Please, let me explain....

To begin, let me mention Laputa.

Laputa is a flying island described in the 1726 book Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift. It is about 4.5 miles in diameter, with an adamantine base, which its highly intelligent inhabitants can maneuver in any direction using magnetic levitation, according to Wikipedia, which goes on to say that Laputa's population consists mainly of educated people, who are fond of mathematics, astronomy, music and technology, but fail to make practical use of their knowledge.

The main geology of what I have to teach about writing is below where my fellow writing professors teach writing. I think of it as the lithosphere of writing skills, or, to spin it another way, a set of hyper-foundational writing skills, skills that, IMHO, students should learn from first grade on up...writing skills they will need when they go to work.

Most of my colleagues can teach rings around me at the "higher" levels.

They teach "process"--plan/draft/revise--grammatical correctness, sentence construction and sentence combining, vocabulary building, and, at the end of their rainbow, rhetoric, argumentation, the essay, and the pursuit of eloquence. All these writing skills are vital, crucial, imperative, important, pivotal, paramount, and all the other predicate adjectives one could muster to link these skills to that which should be praised and even worshipped, aesthetically.

I really do appreciate anyone who dedicates her or his professional energy to getting students to write "better." Please trust me when I say this.

GROUP HUG!

I'm one step beneath almost all writing teachers. I'm intentionally one step behind almost all writing teachers...because I emphasize the very most basic concepts and skills students will need to write at work.

In his book FACTFULNESS (https://www.amazon.com/Factfulness-Reasons-World-Things-Better-ebook/dp/B0756J1LLV/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1534087843&sr=8-1&keywords=factfulness), Hans Rosling warns us about GAP THINKING, about our tendency to engage in US/THEM THINKING. We like to imagine there are GAPS between our idea of the right way or the preferred way and the wrong way when often there are no significant gaps. (Read his book and prepare to be quite a bit happier.)

But I do imagine a GAP between the territory I focus on in teaching writing and the territory most writing teachers focus on when they teach writing. From my point of view, they're up there in Laputa, doing great and tremendous good, teaching students Laputan techniques for writing. But the one thing they're not doing so well is teaching students to write when they land in the workplace.

It's not just my opinion. Articles are myriad about WHY JOHNNY CAN'T WRITE, and the 57 variations thereof. Check the Washington Post. Check Forbes. Check The Atlantic. Check the New York Times. Better yet, Google articles on "poor student writing skills." (Did you get 73,700,000 results, as I did?)

So what's going wrong? How can so many dedicated, highly intelligent writing teachers, who really care whole-heartedly about teaching writing, be failing at this one, fairly humble criterion: "writing well at work?"

Here's where my huffy tone originates.

We should imagine "writing" along a vast spectrum. Let's go all the way back to Aristotle to pick a description of that writing spectrum that withstands the test of time: according to Aristotle, there are three general purposes for writing--to inform, to persuade, and to entertain.

To simplify further, let's cut these general purposes of writing from three to two: to inform and to entertain.

So I ask you to imagine "writing" along this WIDE spectrum. At one end, we write to inform (practical). At the other end, we write to entertain (aesthetic).

Writing to inform (which can be entertaining, I suppose) includes most "writing at work": business texts, emails, blog posts, white papers, proposals, and the huge array of various reports we write for business purposes. Writing to entertain (which can certainly inform) includes poetry, fiction, creative non-fiction, plays, screenplays, etc.

Things like "essays" blog posts (like this one) and marketing materials exist somewhere in the vast middle of this spectrum.

Now imagine this spectrum as a scale from 0 to 1,000. I am focused on the 0, and maybe on the single-digit writing concepts and skills. Whereas most of my colleagues who teach writing, though they may teach humble grammar and sentence construction, are at least in the double digits...it's hard to say exactly. After all, they're up there on Laputa, remember. I'm stuck in the lithosphere, the earth's crust, just below the basement in the great cathedral of writing instruction, below even the foundation itself.

How can this be?

It's irritatingly simple.

I begin by rejecting SQUARE ONE: the way most writing textbooks define communication.

They use the Shannon/Weaver Transmission Model of Communication (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kSq5lw1qDUk).

This model maintains that "communication" occurs when a sender encodes and transmits information (through any "noise" in the system) to a receiver, who must decode the information. The extent to which the receiver successfully decodes what the sender encoded defines the success of the communication.

Shannon/Weaver were describing how radio, telephone, and other signals are transmitted from a transmitting station to a receiving station, not HUMAN communication. Their definition of "information" was just the signals themselves. When you're talking on your smartphone and you experience an interruption in the signal...you might hear every other word the person you're talking to is saying...that's what this model of communication is talking about--JUST THE SIGNAL, not the "content."

Yes, writing is communication. But let's get a bit more complex about what human communication entails. But let's also keep things SIMPLE.

I offer another, very basic, model for human communication: a conversation.

I wish to focus on the most basic dynamics of a conversation, what makes conversations grow and disappear. I want to think of conversations as a loose string of questions and answers. Two or more people conversing ask questions and answer them.

You might think that conversations are built on statements. My friend calls me and says, "Wow. I had a really weird day."

You're right, that's a statement. But it enters what I think of as "conversational space" as the answer to a question that has been unasked but assumed. This friend believes there's always AN OPEN QUESTION between us: "How was my friend's day?" Her statement lands in that open question and opens up my interest and sympathy.

If this friend called a stranger and began a conversation this way, the conversational field would be very different. The stranger would likely respond with some foundational questions, such as, "Who is this?" and "What do you want?" (There are no OPEN QUESTIONS between the two of them.)

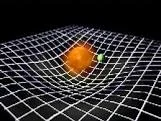

Conversations occur between people in a kind of curved space time...that curved space time is the airy fabric of questions. You might say that these questions create the gravity that holds our conversations together.

It's essential that student writers understand that writing (to inform) is predicated on questions and answers. Without questions, there can be no content...just like the stranger who hears the words "Wow, I had a really weird day!" These signals are meaningless until they're grounded in a question from a real person, a person who becomes REAL only through the stranger's level of interest.

QUESTIONS ARE, AFTER ALL, ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT PHYSICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF OUR "INTEREST"

Without a background of questions, the words we hear have no meaning.

So way down here in the lithosphere, at the zero or first-digit level of "writing-to-inform"---I just call it PRACTICAL WRITING--there's the invisible reality of conversations, i.e., all the words we share with each other (in writing or talking) that exist in a gravitational field of questions and answers; words that can become meaningful only within the curved space time of questions.

Like right now, I hope you're wondering, "What in the heck is this dude talking about?"

Perfect! Questions are always at the threshold of meaningful answers. So keep asking questions.

To be "successful," writing must simulate a conversation.

But how can you do that? After all, when you're writing, the reader isn't there to have a conversation with you! Or maybe she is!

The reader does exist as the background of questions that give context to all the writer's "answers" and make them meaningful.

Without a real reader, you can't have real content. Instead, you have merely Laputan content... transmitted letters and words and punctuation marks and herds of words sent floating weightlessly through the space of nobody's-REALLY-listening (nobody's there to really care). (((And if a tree falls in the forest but there's nobody there to hear it, does it really make a sound???)))

This is why we need to teach students to write only to a REAL reader, with real questions about the issue in question...not to "an audience," phantom, imagined, a figment of the writing assignment.

This basic, earth's crust, concept is the sine qua non of practical writing pedagogy. And it has an important corollary: CONTENT = (reader) question + answer (not just the answer alone).

So here's an argument I have with my writing colleagues. The following two "sentences," my colleagues would argue, have very different content:

- There are no SUBWAY sandwich shops around here where you can have lunch.

- Nope.

But the content of these two "sentences" depends on the question asked. And the "content" provided includes the question as much as the answer.

What if the question were this: Are there any SUBWAY sandwich shops around here where I can have lunch?

You could say that the first "sentence" is more specific or that it reflects the question asked more completely. You could say the second "sentence" is far shorter.

But the actual content can only be understood in terms of both the question and the answer.

Okay. Enough of this (what my wife would call) MAD GERMAN SCIENCE--fill in whatever nationality makes sense to YOU.

While most people think sentence grammar and punctuation are the most basic building blocks of writing instruction, I'd say they're not so basic.

I'd say they're at least in the double digits or even the triple digits on our writing spectrum. That is to say, "writing" must begin with CONTENT, and not Laputan content transmitted from a writer to nobody real. It must be USEFUl content. And usefulness can only happen when there's a REALLY REAL reader who REALLY needs the information to deal with a real issue that's "in question."

So this is where I'm coming from...SQUARE ONE.

By the way (not that anyone asked my opinion), student writing is WAY BETTER than most people think. Most people don't know how to look at writing because their criteria for "effective writing" is not grounded in the primordial content = (reader) questions + answers paradigm.

It's ensconced within a Laputan criteria of GOOD WRITING = surface correctness. (To me, this just seems like an extraordinary claim. I hear and see students talking and texting in animated conversations with friends and fellow students all day long. How could we call their language abilities SUBPAR??? Do they write with "an accent." Do they fail to observe THE "rules" of writing? How quaint. (Uh-oh...there's that tone again. Sorry.)

I'm just insisting as humbly as I can that we offer students a very systematic approach to writing (practical writing) to begin with. They can journey to Laputa as soon as they're ready. There are fabulous things to learn up there about writing aesthetics. Things I probably can't teach as well.

A systems approach acknowledges that all practical writing exists in the curved space time and gravity of CONTENT = (reader's) questions + answers.

Teach students to do "question factoring": factor the issue in question into all the reader's appropriate questions about the issue and then answer them. (Teach them about methodology. Teach them about research. Teach them about evidence. Teach them the performance auditor's 5 Cs--criteria, condition, cause, consequence, corrective action.) Teach them this "critical thinking" and you've taught them a heck of a lot.

Once they know how to generate real CONTENT, a.k.a., USEFUL content, they can learn the grammar of content presentation, all the way up to sentence grammar and punctuation..the lofty skills few ascend to grasp completely (including me).

Come back to earth, is all I'm saying. Join me at the earth's crust. Serve the real reader. Teach practical writing FIRST, then writing to entertain.

Do you know the basic techniques for teaching about the 7 systems that affect usefulness and readability? I call them the HOCs and LOCs.

7. mechanics

6. word choices

5. sentence constructions

4. paragraph configurations

3. document design

2. organization

1. content (ground zero...square one)

Check out my textbook: Mastering Workplace Writing

(https://www.amazon.com/Mastering-Workplace-Writing-Harvey-Lillywhite/dp/0692520082/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1534092953&sr=8-1&keywords=mastering+workplace+writing)

Check out my 200-page ebook--lots of pictures--Mindful Writing at Work

(https://gumroad.com/l/mindfulwriting)

Invite me over to talk to your class/faculty/office.

Tell me what you think: harvey@QCGwrite.com. Why wouldn't you?

Above all, have a conversation, with anyone about anything. Notice the curved space time of questions that reflect your interest that make all those words meaningful.

For those of you on Laputa. Don't forget to wave. I'm the speck in the dirt, jumping up and down, waving back.